|

| HISTORY OF 3D PRINTING |

The history of

3D printing, also known as additive manufacturing, dates back several decades and

has seen significant advancements over time. Here's a brief overview of its history:

- 1960s-1980s: Early Conceptualization

and Development

- The concept of 3D printing began

to take shape in the 1960s with the development of various techniques like

stereolithography and digital light processing (DLP).

- In 1984, Chuck Hull introduced stereolithography,

which involved using UV light to selectively cure liquid photopolymers layer

by layer. This is considered one of the earliest additive manufacturing technologies.

- 1980s-1990s: Emerging Technologies

- In the late 1980s and early 1990s,

several other additive manufacturing methods were developed, including selective

laser sintering (SLS) and fused deposition modeling (FDM).

- In 1992, Carl Deckard developed

selective laser sintering (SLS), a process that involves using a high-powered

laser to selectively fuse powdered materials into a solid structure layer

by layer.

- In 1989, Scott Crump patented the

fused deposition modeling (FDM) process, which extrudes thermoplastic materials

layer by layer to create objects.

- The 2000s: Expansion and Commercialization

- The 2000s saw the expansion of 3D

printing technologies into various industries, including aerospace, automotive,

healthcare, and more.

- Advanced materials beyond plastics,

such as metals and ceramics, began to be used in additive manufacturing.

- Companies like Stratasys and 3D

Systems played pivotal roles in advancing 3D printing technologies and making

them more accessible.

- The 2010s: Mainstream Adoption and Diversification

- The 2010s marked a period of rapid

growth in 3D printing technology adoption, with increased accessibility to

lower-cost printers for businesses and even consumers.

- Industries like healthcare started

using 3D printing for custom medical implants, prosthetics, and even organ

and tissue printing.

- Aerospace and automotive industries

embraced 3D printing for rapid prototyping and production of complex parts.

- Recent Developments and Future Prospects

- In recent years, 3D printing has

continued to evolve with advancements in materials, printing speed, precision,

and the scale of objects that can be printed.

- Large-scale 3D printing and construction

have gained attention for their potential to revolutionize building techniques.

- Bioprinting, the process of creating

living tissues and organs using 3D printing technology, has shown promising

developments in medical and research fields.

Overall, the

history of 3D printing showcases a trajectory of innovation and increasing application

across various industries, making it a transformative technology with a wide range

of possibilities for the future.

3D printing

A three-dimensional printer

3D printing or additive manufacturing is the

construction of a three-dimensional object from a CAD model or a digital 3D model.

It can be done in a variety of processes in which material is deposited, joined, or solidified under computer control, with the material being added together (such as

plastics, liquids, or powder grains being fused), typically layer by layer.

In the 1980s, 3D printing techniques were

considered suitable only for the production of functional or aesthetic prototypes,

and a more appropriate term for it at the time was rapid prototyping. As of 2019,

the precision, repeatability, and material range of 3D printing has increased to

the point that some 3D printing processes are considered viable as an industrial-production

technology, whereby the term additive manufacturing can be used synonymously

with 3D printing. One of the key advantages of 3D printing is the ability

to produce very complex shapes or geometries that would be otherwise infeasible

to construct by hand, including hollow parts or parts with internal truss structures

to reduce weight. Fused deposition modeling (FDM), which uses a continuous filament

of a thermoplastic material, is the most common 3D printing process in use as of

2020.

Terminology

The umbrella term additive manufacturing

(AM) gained popularity in the 2000s, inspired by the theme of materials being

added together (in various ways). In contrast, the term subtractive manufacturing

appeared as a retronym for the large family of machining processes with material

removal as their common process. The term 3D printing still referred

only to the polymer technologies in most minds, and the term AM was more

likely to be used in metalworking and end-use part production contexts than among

polymer, inkjet, or stereolithography enthusiasts.

By the early 2010s, the terms 3D printing

and additive manufacturing evolved senses in which they were alternate umbrella

terms for additive technologies, one being used in popular language by consumer-maker

communities and the media, and the other used more formally by industrial end-use

part producers, machine manufacturers, and global technical standards organizations.

Until recently, the term 3D printing has been associated with machines low

in price or in capability. 3D printing and additive manufacturing

reflect that the technologies share the theme of material addition or joining throughout

a 3D work envelope under automated control. Peter Zelinski, the editor-in-chief

of Additive Manufacturing magazine, pointed out in 2017 that the terms are

still often synonymous in casual usage, but some manufacturing industry experts

are trying to make a distinction whereby additive manufacturing comprises 3D printing

plus other technologies or other aspects of a manufacturing process.

Other terms that have been used as synonyms

or hypernyms have included desktop manufacturing, rapid manufacturing

(as the logical production-level successor to rapid prototyping), and on-demand

manufacturing (which echoes on-demand printing in the 2D sense of printing).

The fact that the application of the adjectives rapid and on-demand

to noun manufacturing was novel in the 2000s reveals the long-prevailing

mental model of the previous industrial era during which almost all production manufacturing

had involved long lead times for laborious tooling development. Today, the term

subtractive has not replaced the term machining, instead complementing

it when a term that covers any removal method is needed. Agile tooling is the use

of modular means to design tooling that is produced by additive manufacturing or

3D printing methods to enable quick prototyping and responses to tooling and fixture

needs. Agile tooling uses a cost-effective and high-quality method to quickly respond

to customer and market needs, and it can be used in hydro-forming, stamping, injection

molding, and other manufacturing processes.

History

1940s and 1950s

The general concept of and procedure to

be used in 3D printing was first described by Murray Leinster in his 1945 short

story “Things Pass By”: "But this constructor is both efficient and flexible.

I feed magnetron plastics - the stuff they make houses and ships of nowadays -

into this moving arm. It makes drawings in the air following drawings it scans with photocells. But plastic comes out of the end of the drawing arm and hardens as

it comes ... following drawings only"

It was also described by Raymond F. Jones

in his story, "Tools of the Trade," published in the November 1950 issue

of Astounding Science Fiction magazine. He referred to it as a "molecular

spray" in that story.

1970s

In 1971, Johannes F Gottwald patented the

Liquid Metal Recorder, U.S. Patent 3596285A, a continuous inkjet metal material

device to form a removable metal fabrication on a reusable surface for immediate

use or salvaged for printing again by remelting. This appears to be the first patent

describing 3D printing with rapid prototyping and controlled on-demand manufacturing

of patterns.

The patent states:

As used herein the

term printing is not intended in a limited sense but includes writing or other symbols,

character, or pattern formation with an ink. The term ink as used is intended

to include not only dye or pigment-containing materials, but any flowable substance

or composition suited for application to the surface for forming symbols, characters,

or patterns of intelligence by marking. The preferred ink is of a hot melt type.

The range of commercially available ink compositions which could meet the requirements

of the invention is not known at the present time. However, satisfactory printing

according to the invention has been achieved with the conductive metal alloy as

ink.

But in terms of material requirements for

such large and continuous displays, if consumed at theretofore known rates, but

increased in proportion to increase in size, the high cost would severely limit

any widespread enjoyment of a process or apparatus satisfying the foregoing objects.

It is therefore an additional object of

the invention to minimize the use of materials in a process of the indicated class.

It is a further object of the invention

that materials employed in such a process be salvaged for reuse.

According to another aspect of the invention,

a combination of writing and the like comprises a carrier for displaying an intelligence

pattern and an arrangement for removing the pattern from the carrier.

In 1974, David E. H. Jones laid out the

concept of 3D printing in his regular column Ariadne in the journal New

Scientist.

1980s

Early additive manufacturing equipment and

materials were developed in the 1980s.

In April 1980, Hideo Kodama of Nagoya Municipal

Industrial Research Institute invented two additive methods for fabricating three-dimensional

plastic models with photo-hardening thermoset polymer, where the UV exposure area

is controlled by a mask pattern or a scanning fiber transmitter. He filed a patent

for this XYZ plotter, which was published on 10 November 1981. (JP S56-144478).

His research results as journal papers were published in April and November of 1981.

However, there was no reaction to the series of his publications. His device was

not highly evaluated in the laboratory and his boss did not show any interest. His

research budget was just 60,000 yen or $545 a year. Acquiring the patent rights

for the XYZ plotter was abandoned, and the project was terminated.

A US 4323756 patent, method of fabricating

articles by sequential deposition, granted on 6 April 1982 to Raytheon Technologies

Corp describes using hundreds or thousands of "layers" of powdered metal

and a laser energy source and represents an early reference to forming "layers"

and the fabrication of articles on a substrate.

On 2 July 1984, American entrepreneur Bill

Masters filed a patent for his computer automated manufacturing process and system

(US 4665492). This filing is on record at the USPTO as the first 3D printing patent

in history; it was the first of three patents belonging to Masters that laid the

foundation for the 3D printing systems used today.

On 16 July 1984, Alain Le Méhauté, Olivier

de Witte, and Jean Claude André filed their patent for the stereolithography process.

The application of the French inventors was abandoned by the French General Electric

Company (now Alcatel-Alsthom) and CILAS (The Laser Consortium). The claimed reason

was "for lack of business perspective".

In 1983, Robert Howard started R.H. Research,

later named Howtek, Inc. in Feb 1984 to develop a color inkjet 2D printer, Pixelmaster,

commercialized in 1986, using Thermoplastic (hot-melt) plastic ink. A team was put

together, 6 members from Exxon Office Systems, Danbury Systems Division, an inkjet

printer startup, and some members of the Howtek, Inc group who became popular figures

in the 3D printing industry. One Howtek member, Richard Helinski (patent US5136515A,

Method and Means for constructing three-dimensional articles by particle deposition,

application 11/07/1989 granted 8/04/1992) formed a New Hampshire company C.A.D-Cast,

Inc, a name later changed to Visual Impact Corporation (VIC) on 8/22/1991. A prototype

of the VIC 3D printer for this company is available with a video presentation showing

a 3D model printed with a single nozzle inkjet. Another employee Herbert Menhennett

formed a New Hampshire company HM Research in 1991 and introduced the Howtek, Inc,

inkjet technology and thermoplastic materials to Royden Sanders of SDI and Bill

Masters of Ballistic Particle Manufacturing (BPM) where he worked for a number of

years. Both BPM 3D printers and SPI 3D printers use Howtek, Inc style Inkjets and

Howtek, Inc style materials. Royden Sanders licensed the Helinksi patent prior to

manufacturing the Modelmaker 6 Pro at Sanders Prototype, Inc (SPI) in 1993. James

K. McMahon who was hired by Howtek, Inc to help develop the inkjet, later worked

at Sanders Prototype and now operates Layer Grown Model Technology, a 3D service

provider specializing in Howtek single nozzle inkjet and SDI printer support. James

K. McMahon worked with Steven Zoltan, a 1972 drop-on-demand inkjet inventor, at Exxon

and has a patent in 1978 that expanded the understanding of the single nozzle design

inkjets (Alpha jets) and help perfect the Howtek, Inc hot-melt inkjets. This Howtek

hot-melt thermoplastic technology is popular with metal investment casting, especially

in the 3D printing jewelry industry. Sanders's (SDI) first Modelmaker 6Pro customer

was Hitchner Corporations, Metal Casting Technology, Inc in Milford, NH a mile from

the SDI facility in late 1993-1995 casting golf clubs and auto engine parts.

On 8 August 1984 a patent, US4575330, assigned

to UVP, Inc., later assigned to Chuck Hull of 3D Systems Corporation was filed,

his own patent for a stereolithography fabrication system, in which individual laminae

or layers are added by curing photopolymers with impinging radiation, particle bombardment,

chemical reaction or just ultraviolet light lasers. Hull defined the process as

a "system for generating three-dimensional objects by creating a cross-sectional

pattern of the object to be formed". Hull's contribution was the STL (Stereolithography)

file format and the digital slicing and infill strategies common to many processes

today. In 1986, Charles "Chuck" Hull was granted a patent for this system,

and his company, 3D Systems Corporation was formed and it released the first commercial

3D printer, the SLA-1, later in 1987 or 1988.

The technology used by most 3D printers

to date-especially hobbyist and consumer-oriented models-is fused deposition modeling,

a special application of plastic extrusion, developed in 1988 by S. Scott Crump

and commercialized by his company Stratasys, which marketed its first FDM machine

in 1992.

Owning a 3D printer in the 1980s cost upwards

of $300,000 ($650,000 in 2016 dollars).

1990s

AM processes for metal sintering or melting

(such as selective laser sintering, direct metal laser sintering, and selective

laser melting) usually went by their own individual names in the 1980s and 1990s.

At the time, all metalworking was done by processes that are now called non-additive

(casting, fabrication, stamping, and machining); although plenty of automation was

applied to those technologies (such as by robot welding and CNC), the idea of a

tool or head moving through a 3D work envelope transforming a mass of raw material

into a desired shape with a toolpath was associated in metalworking only with processes

that removed metal (rather than adding it), such as CNC milling, CNC EDM, and many

others. But the automated techniques that added metal, which would later

be called additive manufacturing, were beginning to challenge that assumption. By

the mid-1990s, new techniques for material deposition were developed at Stanford

and Carnegie Mellon University, including micro casting and sprayed materials.[33]

Sacrificial and support materials had also become more common, enabling new object

geometries.

The term 3D printing originally referred

to a powder bed process employing standard and custom inkjet print heads, developed

at MIT by Emanuel Sachs in 1993 and commercialized by Soligen Technologies, Extrude

Hone Corporation, and Z Corporation.

The year 1993 also saw the start of an inkjet

3D printer company initially named Sanders Prototype, Inc and later named Solidscape,

introducing a high-precision polymer jet fabrication system with soluble support

structures, (categorized as a "dot-on-dot" technique).

In 1995 the Fraunhofer Society developed

the selective laser melting process.

2000s

The Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) printing

process patents expired in 2009. This opened the door for a new wave of companies,

many born from the RepRap community, to start developing commercial FDM 3D printers.

2010s

As the various additive processes matured,

it became clear that soon metal removal would no longer be the only metalworking

process done through a tool or head moving through a 3D work envelope, transforming

a mass of raw material into a desired shape layer by layer. The 2010s were the first

decade in which metal end-use parts such as engine brackets and large nuts would

be grown (either before or instead of machining) in job production rather than obligately

being machined from bar stock or plate. It is still the case that casting, fabrication,

stamping, and machining are more prevalent than additive manufacturing in metalworking,

but AM is now beginning to make significant inroads, and with the advantages of

design for additive manufacturing, it is clear to engineers that much more is to

come.

One place that AM is making significant

inroads is in the aviation industry. With nearly 3.8 billion air travelers in 2016,

the demand for fuel-efficient and easily produced jet engines has never been higher.

For large OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) like Pratt and Whitney (PW) and

General Electric (GE), this means looking towards AM as a way to reduce cost, reduce

the number of nonconforming parts, reduce weight in the engines to increase fuel

efficiency and find new, highly complex shapes that would not be feasible with the

antiquated manufacturing methods. One example of AM integration with aerospace was

in 2016 when Airbus delivered the first of GE's LEAP engines. This engine has

integrated 3D printed fuel nozzles giving them a reduction in parts from 20 to 1,

a 25% weight reduction, and reduced assembly times. A fuel nozzle is the perfect road for additive manufacturing in a jet engine since it allows for optimized

design of the complex internals and it is a low-stress, non-rotating part. Similarly,

in 2015, PW delivered their first AM parts in the PurePower PW1500G to Bombardier.

Sticking to low-stress, non-rotating parts, PW selected the compressor stators and

synch ring brackets to roll out this new manufacturing technology for the first

time. While AM is still playing a small role in the total number of parts in the

jet engine manufacturing process, the return on investment can already be seen by

the reduction in parts, the rapid production capabilities, and the "optimized

design in terms of performance and cost".

As the technology matured, several authors had

begun to speculate that 3D printing could aid in sustainable development in the

developing world.

In 2012, Filabot developed a system for

closing the loop with plastic and allows for any FDM or FFF 3D printer to be able

to print with a wider range of plastics.

In 2014, Benjamin S. Cook and Manos M. Tentzeris

demonstrate the first multi-material, vertically integrated printed electronics

additive manufacturing platform (VIPRE) which enabled 3D printing of functional

electronics operating up to 40 GHz.

As the price of printers started to drop

people interested in this technology had more access and freedom to make what they

wanted. As of 2014, the price for commercial printers was still high with the cost

being over $2,000.

The term "3D printing" originally

referred to a process that deposits a binder material onto a powder bed with inkjet

printer heads layer by layer. More recently, the popular vernacular has started

using the term to encompass a wider variety of additive-manufacturing techniques

such as electron-beam additive manufacturing and selective laser melting. The United

States and global technical standards use the official term additive manufacturing

for this broader sense.

The most commonly used 3D printing process

(46% as of 2018) is a material extrusion technique called fused deposition modeling,

or FDM. While FDM technology was invented after the other two most popular technologies,

stereolithography (SLA) and selective laser sintering (SLS), FDM is typically the

most inexpensive of the three by a large margin, which lends to the popularity of

the process.

2020s

As of 2020, 3D printers have reached the

level of quality and price that allows most people to enter the world of 3D printing.

In 2020 decent-quality printers can be found for less than US$200 for entry-level

machines. These more affordable printers are usually fused deposition modeling (FDM)

printers.

In November 2021 a British patient named

Steve Verze received the world's first fully 3D-printed prosthetic eye from the

Moorfields Eye Hospital in London.

Benefits of 3D printing

Additive manufacturing or 3D printing has

rapidly gained importance in the field of engineering due to its many benefits.

Some of these benefits include enabling faster prototyping, reducing manufacturing

costs, increasing product customization, and improving product quality.

Furthermore, the capabilities of 3D printing

have extended beyond traditional manufacturing, with applications in renewable energy

systems. 3D printing technology can be used to produce battery energy storage systems,

which are essential for sustainable energy generation and distribution.

Another benefit of 3D printing is the technology's

ability to produce complex geometries with high precision and accuracy. This is

particularly relevant in the field of microwave engineering, where 3D printing can

be used to produce components with unique properties that are difficult to achieve

using traditional manufacturing methods.

General principles

Modeling

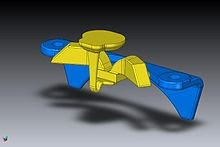

CAD model used for 3D printing

3D models can be generated from 2D pictures taken at a 3D photo booth.

3D printable models may be created with

a computer-aided design (CAD) package, via a 3D scanner, or by a plain digital camera

and photogrammetry software. 3D printed models created with CAD result in relatively

fewer errors than other methods. Errors in 3D printable models can be identified

and corrected before printing. The manual modeling process of preparing geometric

data for 3D computer graphics is similar to plastic arts such as sculpting. 3D scanning

is a process of collecting digital data on the shape and appearance of a real object and creating a digital model based on it.

CAD models can be saved in the stereolithography

file format (STL), a de facto CAD file format for additive manufacturing that stores

data based on triangulations of the surface of CAD models. STL is not tailored for

additive manufacturing because it generates large file sizes of topology-optimized

parts and lattice structures due to the large number of surfaces involved. A newer

CAD file format, the Additive Manufacturing File Format (AMF) was introduced in

2011 to solve this problem. It stores information using curved triangulations.

Printing

Before printing a 3D model from an STL file,

it must first be examined for errors. Most CAD applications produce errors in output

STL files, of the following types:

1. holes

2. faces normals

3. self-intersections

4. noise shells

5. manifold errors

6. overhang issues

A step in the STL generation known as "repair"

fixes such problems in the original model. Generally, STLs that have been produced

from a model obtained through 3D scanning often have more of these errors as 3D scanning is often achieved by point-to-point

acquisition/mapping. 3D reconstruction often includes errors.

Once completed, the STL file needs to be

processed by a piece of software called a "slicer", which converts the

model into a series of thin layers and produces a G-code file containing instructions

tailored to a specific type of 3D printer (FDM printers). This G-code file can then

be printed with 3D printing client software (which loads the G-code and uses it

to instruct the 3D printer during the 3D printing process).

Printer resolution describes layer thickness

and X–Y resolution in dots per inch (dpi) or micrometers (μm). Typical layer thickness

is around 100 μm (250 DPI), although some machines can print layers as thin as 16

μm (1,600 DPI). X-Y resolution is comparable to that of laser printers. The particles

(3D dots) are around 0.01 to 0.1 μm (2,540,000 to 250,000 DPI) in diameter. For

that printer resolution, specifying a mesh resolution of 0.01–0.03 mm and a chord

length ≤ 0.016 mm generates an optimal STL output file for a given model input file.

Specifying higher resolution results in larger files without an increase in print quality.

3:31 Timelapse of

an 80-minute video of an object being made out of PLA using molten polymer deposition

Construction of a model with contemporary

methods can take anywhere from several hours to several days, depending on the method

used and the size and complexity of the model. Additive systems can typically reduce

this time to a few hours, although it varies widely depending on the type of machine

used and the size and number of models being produced simultaneously.

Finishing

Though the printer-produced resolution and

surface finish are sufficient for some applications, post-processing and finishing

methods allow for benefits such as greater dimensional accuracy, smoother surfaces, and other modifications such as coloration.

The surface finish of a 3D printed part can be improved using subtractive methods such as sanding and bead blasting. When smoothing

parts that require dimensional accuracy, it is important to take into account the

volume of the material being removed.

Some printable polymers, such as acrylonitrile

butadiene styrene (ABS), allow the surface finish to be smoothed and improved using

chemical vapor processes based on acetone or similar solvents.

Some additive manufacturing techniques can

benefit from annealing annealing as a post-processing step. Annealing a 3D-printed

part allows for better internal layer bonding due to the recrystallization of the part

and allows for an increase in mechanical properties, some of which are fracture

toughness, flexural strength, impact resistance, and heat resistance. Annealing

a component may not be suitable for applications where dimensional accuracy is required,

as it can introduce warpage or shrinkage due to heating and cooling.

Additive/Subtractive Hybrid Manufacturing

(ASHM) is a method that involves producing a 3D printed part and using machining

(subtractive manufacturing) to remove material. Machining operations can be completed

after each layer, or after the entire 3D print has been completed depending on the

application requirements. These hybrid methods allow for 3D-printed parts to achieve

better surface finishes and dimensional accuracy.

The layered structure of traditional additive

manufacturing processes leads to a stair-stepping effect on part surfaces that

are curved or tilted with respect to the building platform. The effect strongly depends

on the layer height used, as well as the orientation of a part surface inside the

building process. This effect can be minimized using "variable layer heights"

or "adaptive layer heights". These methods decreased the layer height

in places where higher quality is needed.

Painting a 3D-printed part offers a range

of finishes and appearances that may not be achievable through most 3D printing

techniques. The process typically involves several steps such as surface preparation,

priming, and painting. These steps help prepare the surface of the part and ensure

the paint adheres properly.

Some additive manufacturing techniques are

capable of using multiple materials simultaneously. These techniques are able to

print in multiple colors and color combinations simultaneously and can produce

parts that may not necessarily require painting.

Some printing techniques require internal

supports to be built to support overhanging features during construction. These

supports must be mechanically removed or dissolved if using a water-soluble support

material such as PVA using after completing a print.

Some commercial metal 3D printers involve

cutting the metal component off the metal substrate after deposition. A new process

for GMAW 3D printing allows for substrate surface modifications to remove aluminum

or steel.

Multi-material 3D

printing

A multi-material 3DBenchy.

Efforts to achieve multi-material 3D printing

range from enhanced FDM-like processes like VoxelJet to novel voxel-based printing

technologies like layered assembly.

A drawback of many existing 3D printing

technologies is that they only allow one material to be printed at a time, limiting

many potential applications which require the integration of different materials

in the same object. Multi-material 3D printing solves this problem by allowing objects

of complex and heterogeneous arrangements of materials to be manufactured using

a single printer. Here, a material must be specified for each voxel (or 3D printing

pixel element) inside the final object volume.

The process can be fraught with complications,

however, due to the isolated and monolithic algorithms. Some commercial devices

have sought to solve these issues, such as building a Spec2Fab translator, but the

progress is still very limited. Nonetheless, in the medical industry, the concept

of 3D-printed pills and vaccines has been presented. With this new concept, multiple

medications can be combined, which will decrease many risks. With more and more

applications of multi-material 3D printing, the costs of daily life and high technology

development will become inevitably lower.

Metallographic materials of 3D printing

are also being researched. By classifying each material, CIMP-3D can systematically

perform 3D printing with multiple materials.

4D printing

Using 3D printing and multi-material structures

in additive manufacturing has allowed for the design and creation of what is called

4D printing. 4D printing is an additive manufacturing process in which the printed

object changes shape with time, temperature, or some other type of stimulation.

4D printing allows for the creation of dynamic structures with adjustable shapes,

properties, or functionality. The smart/stimulus-responsive materials that are created

using 4D printing can be activated to create calculated responses such as self-assembly,

self-repair, multi-functionality, reconfiguration, and shape-shifting. This allows

for customized printing of shape-changing and shape-memory materials.

4D printing has the potential to find new

applications and uses for materials (plastics, composites, metals, etc.) and will

create new alloys and composites that were not viable before. The versatility of

this technology and materials can lead to advances in multiple fields of industry,

including space, commercial, and the medical field. The repeatability, precision,

and material range for 4D printing must increase to allow the process to become

more practical throughout these industries.

To become a viable industrial production

option, there are a couple of challenges that 4D printing must overcome. The challenges

of 4D printing include the fact that the microstructures of these printed smart

materials must be close to or better than the parts obtained through traditional

machining processes. New and customizable materials need to be developed that have

the ability to consistently respond to varying external stimuli and change to their

desired shape. There is also a need to design new software for the various technique

types of 4D printing. The 4D printing software will need to take into consideration

the base smart material, printing technique, and structural and geometric requirements

of the design.

Applications

3D printing or additive manufacturing has

been used in manufacturing, medical, industry, and sociocultural sectors (e.g. Cultural

Heritage) to create successful commercial technology. More recently, 3D printing

has also been used in the humanitarian and development sector to produce a range

of medical items, prosthetics, spares, and repairs. The earliest application of additive

manufacturing was on the toolroom end of the manufacturing spectrum. For example,

rapid prototyping was one of the earliest additive variants, and its mission was

to reduce the lead time and cost of developing prototypes of new parts and devices,

which was earlier only done with subtractive toolroom methods such as CNC milling,

turning, and precision grinding. In the 2010s, additive manufacturing entered production

to a much greater extent.

In cars, trucks, and aircraft, Additive

Manufacturing is beginning to transform both (1) unibody and fuselage design and

production and (2) powertrain design and production. For example, General Electric

uses high-end 3D printers to build parts for turbines. Many of these systems are

used for rapid prototyping before mass production methods are employed. Other prominent

examples include:

- In early 2014, Swedish supercar manufacturer

Koenigsegg announced the One:1, a supercar that utilizes many components that were

3D printed. Urbee is the first car produced using 3D printing (the bodywork and

car windows were "printed").

- In 2014, Local Motors debuted Strati, a

functioning vehicle that was entirely 3D printed using ABS plastic and carbon fiber,

except the powertrain.

- In May 2015 Airbus announced that its new

Airbus A350 XWB included over 1000 components manufactured by 3D printing.

- In 2015, a Royal Air Force Eurofighter Typhoon

fighter jet flew with printed parts. The United States Air Force has begun to work

with 3D printers, and the Israeli Air Force has also purchased a 3D printer to print

spare parts.

- In 2017, GE Aviation revealed that it had

used design for additive manufacturing to create a helicopter engine with 16 parts

instead of 900, with a great potential impact on reducing the complexity of supply

chains.

Firearm industry

AM's impact on firearms involves two dimensions:

new manufacturing methods for established companies, and new possibilities for the

making of do-it-yourself firearms. In 2012, the US-based group Defense Distributed

disclosed plans to design a working plastic 3D printed firearm "that could

be downloaded and reproduced by anybody with a 3D printer." After Defense Distributed

released its plans, questions were raised regarding the effects that 3D printing

and widespread consumer-level CNC machining may have on gun control effectiveness.

Moreover, armor design strategies can be enhanced by taking inspiration from nature

and prototyping those designs easily possible using additive manufacturing.

Health sector

Surgical uses of 3D printing-centric therapies

have a history beginning in the mid-1990s with anatomical modeling for bony reconstructive

surgery planning. Patient-matched implants were a natural extension of this work,

leading to truly personalized implants that fit one unique individual. Virtual planning

of surgery and guidance using 3D-printed, personalized instruments have been applied

to many areas of surgery including total joint replacement and craniomaxillofacial

reconstruction with great success. One example of this is the bioresorbable tracheal

splint to treat newborns with tracheobronchomalacia developed at the University

of Michigan. The use of additive manufacturing for serialized production of orthopedic

implants (metals) is also increasing due to the ability to efficiently create porous

surface structures that facilitate osseointegration. The hearing aid and dental

industries are expected to be the biggest area of future development using custom

3D printing technology.

3D printing is not just limited to inorganic

materials; there have been a number of biomedical advancements made possible by

3D printing. As of 2012, 3D bio-printing technology has been studied by biotechnology

firms and academia for possible use in tissue engineering applications in which

organs and body parts are built using inkjet printing techniques. In this process,

layers of living cells are deposited onto a gel medium or sugar matrix and slowly

built up to form three-dimensional structures including vascular systems. 3D printing

has been considered as a method of implanting stem cells capable of generating new

tissues and organs in living humans. In 2018, 3D printing technology was used for

the first time to create a matrix for cell immobilization in fermentation. Propionic

acid production by Propionibacterium acidipropionici immobilized on 3D-printed

nylon beads was chosen as a model study. It was shown that those 3D-printed beads

were capable of promoting high-density cell attachment and propionic acid production,

which could be adapted to other fermentation bioprocesses.

3D printing has also been employed by researchers

in the pharmaceutical field. During the last few

Medical equipment

During the COVID-19 pandemic, 3d printers

were used to supplement the strained supply of PPE through volunteers using their

personally owned printers to produce various pieces of personal protective equipment

(i.e. frames for face shields).

Soft actuators

3D printed soft actuators are a growing application

of 3D printing technology that has found its place in the 3D printing applications.

These soft actuators are being developed to deal with soft structures and organs, especially in biomedical sectors and where the interaction between humans and robots

is inevitable. The majority of the existing soft actuators are fabricated by conventional

methods that require manual fabrication of devices, post-processing/assembly, and

lengthy iterations until the maturity of the fabrication is achieved. Instead of the

tedious and time-consuming aspects of the current fabrication processes, researchers

are exploring an appropriate manufacturing approach for the effective fabrication of

soft actuators. Thus, 3D-printed soft actuators are introduced to revolutionize

the design and fabrication of soft actuators with custom geometrical, functional,

and control properties in a faster and inexpensive approach. They also enable the incorporation

of all actuator components into a single structure eliminating the need to use external

joints, adhesives, and fasteners.

Circuit boards

Circuit board manufacturing involves multiple

steps which include imaging, drilling, plating, solder mask coating, nomenclature

printing, and surface finishes. These steps include many chemicals such as harsh

solvents and acids. 3D printing circuit boards remove the need for many of these

steps while still producing complex designs. Polymer ink is used to create the layers

of the build while silver polymer is used for creating the traces and holes used

to allow electricity to flow. Current circuit board manufacturing can be a tedious

process depending on the design. Specified materials are gathered and sent into

inner layer processing where images are printed, developed, and etched. The etch

cores are typically punched to add lamination tooling. The cores are then prepared

for lamination. The stack-up, the buildup of a circuit board, is built and sent

into lamination where the layers are bonded. The boards are then measured and drilled.

Many steps may differ from this stage however for simple designs, the material goes

through a plating process to plate the holes and surface. The outer image is then

printed, developed, and etched. After the image is defined, the material must get

coated with a solder mask for later soldering. Nomenclature is then added so components

can be identified later. Then the surface finish is added. The boards are routed

out of panel form into their singular or array form and then electrically tested.

Aside from the paperwork which must be completed which proves the boards meet specifications,

the boards are then packed and shipped. The benefits of 3D printing would be that

the final outline is defined from the beginning, no imaging, punching, or lamination

is required, and electrical connections are made with the silver polymer which eliminates

drilling and plating. The final paperwork would also be greatly reduced due to the

lack of materials required to build the circuit board. Complex designs which may

take weeks to complete through normal processing can be 3D printed, greatly reducing

manufacturing time.

A 3D selfie in 1:20

scale printed using gypsum-based printing

Hobbyists

In 2005, academic journals had begun to

report on the possible artistic applications of 3D printing technology. Off-the-shelf machines were increasingly capable of producing practical household applications,

for example, ornamental objects. Some practical examples include a working clock

and gears printed for home woodworking machines among other purposes. Web sites

associated with home 3D printing tended to include backscratchers, coat hooks, door

knobs, etc. As of 2017, domestic 3D printing was reaching a consumer audience beyond

hobbyists and enthusiasts. Several projects and companies are making efforts to

develop affordable 3D printers for home desktop use. Much of this work has been

driven by and targeted at DIY/maker/enthusiast/early adopter communities, with additional

ties to the academic and hacker communities.

Sped on by decreases in price and increases

in quality, As of 2019 an estimated 2 million people worldwide have purchased a

3D printer for hobby use.

Legal aspects

Intellectual property

3D printing has existed for decades within

certain manufacturing industries where many legal regimes, including patents, industrial

design rights, copyrights, and trademarks may apply. However, there is not much

jurisprudence to say how these laws will apply if 3D printers become mainstream

and individuals or hobbyist communities begin manufacturing items for personal use,

for non-profit distribution, or for sale.

Any of the mentioned legal regimes may prohibit

the distribution of the designs used in 3D printing or the distribution or sale

of the printed item. To be allowed to do these things, where active intellectual

property was involved, a person would have to contact the owner and ask for a license,

which may come with conditions and a price. However, many patent, design, and copyright

laws contain a standard limitation or exception for "private", or "non-commercial"

use of inventions, designs, or works of art protected under intellectual property

(IP). That standard limitation or exception may leave such private, non-commercial

uses outside the scope of IP rights.

Patents cover inventions including processes,

machines, manufacturing, and compositions of matter and have a finite duration which

varies between countries, but generally 20 years from the date of application. Therefore,

if a type of wheel is patented, printing, using, or selling such a wheel could be

an infringement of the patent.

Copyright covers an expression in a tangible,

fixed medium and often lasts for the life of the author plus 70 years thereafter.

For example, a sculptor retains copyright over a statue, such that other people

cannot then legally distribute designs to print an identical or similar statue without

paying royalties, waiting for the copyright to expire, or working within a fair

use exception.

When a feature has both artistic (copyrightable)

and functional (patentable) merits when the question has appeared in US court,

the courts have often held the feature is not copyrightable unless it can be separated

from the functional aspects of the item. In other countries, the law and the courts

may apply a different approach allowing, for example, the design of a useful device

to be registered (as a whole) as an industrial design on the understanding that,

in case of unauthorized copying, only the non-functional features may be claimed

under design law whereas any technical features could only be claimed if covered

by a valid patent.

Gun legislation

and administration

The US Department of Homeland Security and

the Joint Regional Intelligence Center released a memo stating that "significant

advances in three-dimensional (3D) printing capabilities, availability of free digital

3D printable files for firearms components, and difficulty regulating file sharing

may present public safety risks from unqualified gun seekers who obtain or manufacture

3D printed guns" and that "proposed legislation to ban 3D printing of

weapons may deter, but cannot completely prevent their production. Even if the

practice is prohibited by new legislation, online distribution of these 3D printable

files will be as difficult to control as any other illegally traded music, movie, or software files."

Attempting to restrict the distribution

of gun plans via the Internet has been likened to the futility of preventing the

widespread distribution of DeCSS, which enabled DVD ripping. After the US government

had Defense Distributed take down the plans, they were still widely available via

the Pirate Bay and other file-sharing sites. Downloads of the plans from the UK,

Germany, Spain, and Brazil were heavy. Some US legislators have proposed regulations

on 3D printers to prevent them from being used for printing guns. 3D printing advocates

have suggested that such regulations would be futile, could cripple the 3D printing

industry, and could infringe on free speech rights, with early pioneer of 3D printing

professor Hod Lipson suggesting that gunpowder could be controlled instead.

Internationally, where gun controls are

generally stricter than in the United States, some commentators have said the impact

may be more strongly felt since alternative firearms are not as easily obtainable.

Officials in the United Kingdom have noted that producing a 3D-printed gun would

be illegal under their gun control laws. Europol stated that criminals have access

to other sources of weapons but noted that as technology improves, the risks of

an effect would increase.

Aerospace regulation

In the United States, the FAA has anticipated

a desire to use additive manufacturing techniques and has been considering how best

to regulate this process. The FAA has jurisdiction over such fabrication because

all aircraft parts must be made under FAA production approval or under other FAA

regulatory categories. In December 2016, the FAA approved the production of a 3D-printed fuel nozzle for the GE LEAP engine. Aviation attorney Jason Dickstein has

suggested that additive manufacturing is merely a production method, and should

be regulated like any other production method. He has suggested that the FAA's focus

should be on guidance to explain compliance, rather than on changing the existing

rules and that existing regulations and guidance permit a company "to develop

a robust quality system that adequately reflects regulatory needs for quality assurance".

Impact

Additive manufacturing, starting with today's

infancy period, requires manufacturing firms to be flexible, ever-improving users

of all available technologies to remain competitive. Advocates of additive manufacturing

also predict that this arc of technological development will counter globalization,

as end users will do much of their own manufacturing rather than engage in trade

to buy products from other people and corporations. The real integration of the

newer additive technologies into commercial production, however, is more a matter

of complementing traditional subtractive methods rather than displacing them entirely.

The futurologist Jeremy Rifkin claimed that

3D printing signals the beginning of a third industrial revolution, succeeding the

production line assembly that dominated manufacturing starting in the late 19th

century.

Social change

Since the 1950s, a number of writers and

social commentators have speculated in some depth about the social and cultural

changes that might result from the advent of commercially affordable additive manufacturing

technology. In recent years, 3D printing is creating a significant impact in the humanitarian

and development sector. Its potential to facilitate distributed manufacturing is

resulting in supply chain and logistics benefits, by reducing the need for transportation,

warehousing, and wastage. Furthermore, social and economic development is being advanced

through the creation of local production economies.

Others have suggested that as more and more

3D printers start to enter people's homes, the conventional relationship between

the home and the workplace might get further eroded. Likewise, it has also been

suggested that, as it becomes easier for businesses to transmit designs for new

objects around the globe, so the need for high-speed freight services might also

become less. Finally, given the ease with which certain objects can now be replicated,

it remains to be seen whether changes will be made to current copyright legislation

so as to protect intellectual property rights with the new technology widely available.

As 3D printers became more accessible to

consumers, online social platforms have developed to support the community. This

includes websites that allow users to access information such as how to build a

3D printer, as well as social forums that discuss how to improve 3D print quality

and discuss 3D printing news, as well as social media websites that are dedicated

to sharing 3D models. RepRap is a wiki-based website that was created to hold all

information on 3D printing and has developed into a community that aims to bring

3D printing to everyone. Furthermore, there are other sites such as Pinshape, Thingiverse, and MyMiniFactory, which were created initially to allow users to post 3D files

for anyone to print, allowing for decreased transaction costs of sharing 3D files.

These websites have allowed greater social interaction between users, creating communities

dedicated to 3D printing.

Larry Summers wrote about the "devastating

consequences" of 3D printing and other technologies (robots, artificial intelligence,

etc.) for those who perform routine tasks. In his view, "already there are

more American men on disability insurance than doing production work in manufacturing.

And the trends are all in the wrong direction, particularly for the less skilled,

as the capacity of capital embodying artificial intelligence to replace white-collar

as well as blue-collar work will increase rapidly in the years ahead." Summers

recommends more vigorous cooperative efforts to address the "myriad devices"

(e.g., tax havens, bank secrecy, money laundering, and regulatory arbitrage) enabling

the holders of great wealth to "a paying" income and estate taxes, and

to make it more difficult to accumulate great fortunes without requiring "great

social contributions" in return, including: more vigorous enforcement of anti-monopoly

laws, reductions in "excessive" protection for intellectual property,

greater encouragement of profit-sharing schemes that may benefit workers and give

them a stake in wealth accumulation, strengthening of collective bargaining arrangements,

improvements in corporate governance, strengthening of financial regulation to eliminate

subsidies to financial activity, easing of land-use restrictions that may cause

the real estate of the rich to keep rising in value, better training for young people

and retraining for displaced workers, and increased public and private investment

in infrastructure development -e.g., in energy production and transportation.

Michael Spence wrote that "Now comes

a ... powerful, wave of digital technology that is replacing labor in increasingly

complex tasks. This process of labor substitution and disintermediation has been

underway for some time in service sectors -think of ATMs, online banking, enterprise

resource planning, customer relationship management, mobile payment systems, and

much more. This revolution is spreading to the production of goods, where robots

and 3D printing are displacing labor." In his view, the vast majority of the

cost of digital technologies comes at the start, in the design of hardware (e.g.

3D printers) and, more important, in creating the software that enables machines

to carry out various tasks. "Once this is achieved, the marginal cost of the

hardware is relatively low (and declines as scale rises), and the marginal cost

of replicating the software is essentially zero. With a huge potential global market

to amortize the upfront fixed costs of design and testing, the incentives to invest

[in digital technologies] are compelling."

Naomi Wu regards the usage of 3D printing

in the Chinese classroom (where rote memorization is standard) to teach design principles

and creativity as the most exciting recent development of the technology, and more

generally regards 3D printing as being the next desktop publishing revolution.

0 Comments